Ecology and Physical Setting

Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests are found in the colder regions of the state, particularly in the Northeastern Highlands, Northern Green Mountains, and Southern Green Mountains. In northern Vermont, they can be matrix-forming. They are found in cold pockets, where cool air settles and where soils are especially moist. Thus, in an area where mountains and cold lowland pockets occur side by side, as in the Northeastern Highlands, one sees hardwood forests sandwiched between areas of softwood: spruce and fir will dominate at both the highest and lowest elevations, and hardwoods will dominate on the middle slopes between. Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests are often found adjacent to and grading into wetlands such as Black Spruce Swamps. Where extensive areas of Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest occur, as in Maine and Canada, they are known as Spruce-Fir Flats.

Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest can be a confusing name for these forests because they are also common at fairly high elevations in the plateau area of the Southern Green Mountains. Although the elevation is high (2,000 feet or more), these forests are tucked into cold pockets and depressions, where the high winds and frequent fog of mountain summits are not felt. In species composition, soil characteristics, and ecological processes, they are distinct from Montane Spruce-Fir Forests.

Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest is a variable community. We recognize two variants: one with wetter soils and one with better-drained soils. Here we describe the moist-soil type; the other is described under “Variants.”

Parent materials in these forests are basal till or lacustrine sediments. Soils are spodosols—acidic, leached soils that are low in fertility. They are moderately well drained to somewhat poorly drained. The depth of the basal till is typically less than 20 inches. Large boulders are a common sight in this community.

Natural disturbance regimes vary with soil moisture and texture. In wetter areas, shallow rooting contributes to windthrow, leaving single-tree gaps and a microtopography of hummocks and hollows. In rare cases where storms are very severe, large areas of blowdown can occur. Ice damage can influence these forests. In drier areas, fire can be an important natural process. Other natural disturbances include flooding and felling of trees by beaver, and infestations of spruce budworm and spruce bark beetle.

Vegetation

In most places, red spruce and balsam fir are the late-successional dominants. Given the variability of soils within this forest type, however, species composition can vary considerably. Black spruce is common where soils are wetter. White pine can be a component of the canopy in well-drained soils. Hardwoods such as red maple, yellow birch, and paper birch can be mixed in as well. White spruce is absent from southern Vermont but is common as a mid-successional tree in the Northeastern Highlands and to the north in Maine and Canada.

Shrubs such as mountain holly and wild raisin are scattered in the understory. The ground layer is often dominated by mosses and liverworts. Herbs such as common wood sorrel, bluebead lily, and shining clubmoss are scattered about, but the dense shade makes them scarce. Overall plant diversity is low in comparison with other forest types.

Wildlife Habitat

Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests provide some of Vermont’s most extensive boreal habitat, especially in the Nulhegan Basin of the Northeastern Highlands. Here, the Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest is interspersed with wetlands, including Spruce-Fir-Tamarack Swamps, Black Spruce Swamps, peatlands, and beaver ponds, forming a rich mosaic of habitats. There are several rare nesting birds that are at the southern edge of their range in the Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest of the Nulhegan Basin, including spruce grouse, Canada jay, black-backed woodpecker, and boreal chickadee. Other highly characteristic species are yellow-bellied flycatcher, Canada warbler, and olive-sided flycatcher.

In northeastern Vermont, Canadian lynx and American marten are established in the Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests and associated swamps. Both species prefer large tracts of forest that are unfragmented by roads and development. Lynx and marten are both well adapted to deep winter snow. Snowshoe hare, the primary prey of lynx, is common in Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests. Red squirrels are also common. The dense evergreen canopy of these forests provides winter shelter for white-tailed deer, habitat that is especially important in the coldest and snowiest areas of Vermont.

Successional Trends

Succession in Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests can take several paths, creating confusion for the ecologist or forester trying to understand the natural vegetation of a site.

On better-drained sites, repeated harvest of softwoods for pulp can create a forest that resembles a Northern Hardwood Forest, as spruce and fir are removed. Softwoods will eventually come into the understory and may ultimately return to a place of dominance, but this process can take a long time. In the interim it can be difficult to determine whether a hardwood forest is “natural” or a result of past logging practices.

On the other hand, softwood species such as red and white spruce, which are normally thought of as late-successional species, can be quite successful as pioneers in old fields, as can balsam fir and northern white cedar. These species do well where mineral soil has not been exposed. The heavy seeds make their way into the sod, and the large seedlings are able to compete with field grasses. Thus, a site that was originally softwood may return directly to softwood domination, with no intermediate successional step. Or, a site that was originally dominated by hardwoods may be converted to softwoods, at least temporarily.

Where natural processes have prevailed, succession in Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests is perhaps a bit more predictable. On riverbanks, steep slopes, and sites where soil disturbance accompanies the natural removal of trees, shade-intolerant hardwoods such as paper birch, aspen, and pin cherry tend to come in first, growing quickly and creating a forest canopy in only a few years. Later, these will be replaced by spruce and fir, with yellow birch and red maple mixed in. Eventually, in the absence of disturbance, red spruce, black spruce, and white pine will dominate, depending on the nature of the substrate.

Variants

- Well-Drained Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest is found on benches, plateaus, shorelines, and glacial outwash. Soils are moderately well-drained to excessively drained sands or gravels. White pine can be a late-successional dominant in these areas; black spruce is generally absent. Fire may play a role in natural forests of this type, few of which remain.

Related Communities

- Montane Spruce-Fir Forest is found at high elevations on mountaintops where fog and wind are important ecological factors. Soils are cold and acid-leached.

- Black Spruce Swamp is often adjacent to the wetter examples of this community and intergrades with it. These wetlands have very poorly drained organic soils.

- Spruce-Fir-Tamarack Swamp is closely related to wet Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest, and the two communities often intergrade.

Conservation Status and Management Considerations

Most Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests in Vermont have been logged in the past, some quite heavily. No old forest

examples are known. Some of the finest examples are on protected lands within the Nulhegan Basin of the Northeastern Highlands. Management of these forests is a complex issue. To protect natural biological diversity, management must recognize and mimic natural ecological processes. Hardwoods and softwoods should be favored in the same proportion as they would be by nature. Soil disturbance should be minimized, especially in wet areas.

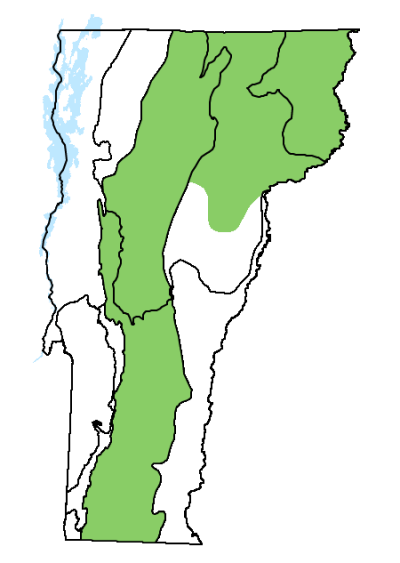

Distribution/Abundance

Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests are common in the lowlands of the Northeastern Highlands, lowlands within the Northern Green Mountains, the plateau area of the Southern Green Mountains, and scattered locations in the Northern Vermont Piedmont. The community is common in northern Maine and in the Adirondacks, as well as in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and parts of Québec. Related communities are found in a broad band of boreal forest extending across Canada.

Characteristic Plants

Trees

Abundant Species

Red spruce – Picea rubens

Balsam fir – Abies balsamea

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

White pine – Pinus strobus

Yellow birch – Betula alleghaniensis

Paper birch – Betula papyrifera

Black spruce – Picea mariana

White spruce – Picea glauca

Northern white cedar – Thuja occidentalis

Tamarack – Larix laricina

Shrubs

Abundant Species

Striped maple – Acer pensylvanicum

Hobblebush – Viburnum lantanoides

Mountain holly – Ilex mucronata

Wild raisin – Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides

Sheep laurel – Kalmia angustifolia

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

Labrador tea – Rhododendron groenlandicum

Leatherleaf – Chamaedaphne calyculata

Mountain maple – Acer spicatum

American mountain ash – Sorbus americana

Bartram’s shadbush – Amelanchier bartramiana

Velvetleaf blueberry – Vaccinium myrtilloides

Herbs

Abundant Species

Common wood sorrel – Oxalis montana

Bluebead lily – Clintonia borealis

Bunchberry – Cornus canadensis

Shining clubmoss – Huperzia lucidula

Whorled aster – Oclemena acuminata

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

Twinflower – Linnaea borealis

Goldthread – Coptis trifolia

Canada mayflower – Maianthemum canadense

Pink lady’s slipper – Cypripedium acaule

Bryophytes and Lichens

found in Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest.

Schreber’s moss – Pleurozium schreberi

Stair-step moss – Hylocomium splendens

Knight’s plume moss – Ptilium crista-castrensis

Common fern moss – Thuidium delicatulum

Pincushion moss – Leucobryum glaucum

Windswept moss – Dicranum spp.

Three-lobed bazzania – Bazzania trilobata

Reindeer lichen – Cladonia/Cladina spp.

Rare and Uncommon Plants

Mountain cranberry – Vaccinium vitis-idaea

Moose dung moss – Splachnum ampullaceum

Associated Animals

Smoky shrew – Sorex fumeus

Southern red-backed vole – Myodes gapperi

Red squirrel – Tamiasciurus hudsonicus

Northern flying squirrel – Glaucomys sabrinus

Fisher – Pekania pennanti

Moose – Alces americanus

White-tailed deer – Odocoileus virginianus

Snowshoe hare – Lepus americanus

American woodcock – Scolopax minor

Canada warbler – Cardellina canadensis

Olive-sided flycatcher – Contopus cooperi

Yellow-bellied flycatcher – Empidonax flaviventris

Yellow-rumped warbler – Setophaga coronata

Blackburnian warbler – Setophaga fusca

Swainson’s thrush – Catharus ustulatus

Red-breasted nuthatch – Sitta canadensis

Ruby-crowned kinglet – Regulus calendula

Golden-crowned kinglet – Regulus satrapa

Ruffed grouse – Bonasa umbellus

Rare and Uncommon Animals

American marten – Martes americana

Canadian lynx – Lynx canadensis

Southern bog lemming – Synaptomys cooperi

Rock vole – Microtus chrotorrhinus

Black-backed woodpecker – Picoides arcticus

Rusty blackbird – Euphagus carolinus

Spruce grouse – Falcipennis canadensis

Canada jay – Perisoreus canadensis

Cape May warbler – Setophaga tigrina

Boreal chickadee – Poecile hudsonicus

White-winged crossbill – Loxia leucoptera

Northern saw-whet owl – Aegolius acadicus

Boreal long-lipped tiger beetle – Cicindela longilabris

Places to Visit

Nulhegan Basin, Lewis, Silivio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Victory Basin, Victory, Victory Basin Wildlife Management Area, Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department

Lye Brook Wilderness, Sunderland, Green Mountain National Forest