This page covers questions frequently asked about white-tailed deer. It includes:

- White-tailed Deer Population

- White-tailed Deer Habitat

- White-tailed Deer Management

- White-Tailed Deer Hunting

- White-tailed Deer Conflicts

- Vermont's Deer Herd Health

White-tailed Deer Population

How many deer are there in Vermont?

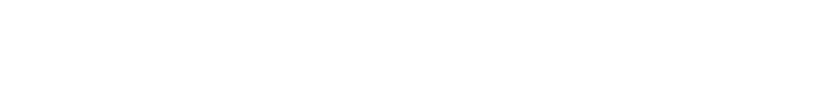

The pre-hunt estimate for 2021 was approximately 133,000 deer.

How does that compare to past years?

The population estimate for 2021 is somewhat lower than the most recent years but is about average for the past 10-20 years.

Why can’t we have more deer like in the 1960s or 1970s?

In some parts of Vermont, particularly the northern Champlain Valley and Orleans County, there are far more deer now than there were in the 1960s or 1970s or at any other time in the past several hundred years.

In most of the state, forest habitats were younger in the mid-century and could support more deer. However, there was still an overabundance of deer at the time, causing them to be in poor condition and more susceptible to winterkill, and also forcing deer to over-browse and damage their habitat.

Deer are healthier now, with adult females producing more fawns on average than in the 1960s and 1970s. Also, deer are now heavier going into winter, and deer wintering areas are in better condition, which means that fewer deer die of winter starvation.

It is Vermont law that we protect and promote the health of our deer herd; this is done by taking the right number of does from the right areas to keep deer from becoming overabundant. Overall, there are fewer deer in the state now, but this is considered a biological success story, not a failure.

Are Vermont’s deer healthy?

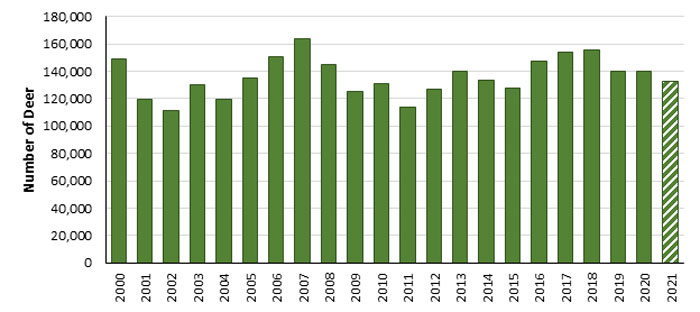

Yes, but... Beginning in 1979 with control of antlerless deer hunting, the department took actions to reduce the overabundant deer herd, let habitats recover through the 1980s, and let the herd grow again in the 1990s. This has resulted in a much healthier deer herd as evidenced by reproductive rates and their ability to recover from harsh winters. However, as our forests mature and the overall quality of Vermont’s deer habitat declines, we are beginning to see declines in the physical condition of deer in some areas (see figure below). Deer numbers may not have increased substantially, but the declining habitat can no longer support as many deer.

Vermont’s deer are not affected with major disease issues and we are working diligently to keep diseases such as Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) out of the state.

What does it mean when you say deer are overabundant?

The term overabundant simply means that there are more deer than the habitat can support long-term, or there are more deer than people are willing to tolerate. In other words, deer have exceeded the ecological or social carrying capacity, or both. Overabundant does not necessarily mean there are a lot of deer. In areas of poor habitat quality, there can be too many deer for that habitat to support even when deer density is relatively low.

Do coyotes regulate deer numbers in Vermont?

Not unlike other predators such as fisher, bobcat, and bear, coyotes do kill deer. Most of these deer are young fawns or debilitated deer in late winter. Research has shown that about half of fawns will die during the first couple months of their life. This is true in areas with or without predators. The difference is whether most of them die of starvation or predation. In other words, fawn predation is mostly compensatory – that is, it does not add to total mortality but instead replaces other causes. Recent research is finding that this is also true of coyote predation on adult deer, particularly during the winter. Predation increases during severe winters, when deep snow limits deer movement, but it has essentially replaced starvation as the primary cause of death. In mild winters, predation of adult deer is minimal.

Although the degree to which predation affects the overall deer herd is commonly disputed, predation rates are an important consideration in deer management and are accounted for in all management decisions. The abundance of predators on the landscape only highlights the need for maintaining a healthy deer herd and functioning, high quality deer habitat. To be clear, predators can occasionally impact local deer herds, but they do not regulate deer populations at larger scales like a wildlife management unit.

Will reducing predators help the deer herd?

No. Predators do not regulate deer numbers in Vermont. While certain predators may occasionally impact local deer populations, this is often related to poor habitat quality or other underlying factors.

I’ve found a small fawn and it looks abandoned. What should I do?

Many mammals including deer naturally leave their young alone most of the time during the first month of life. The fawns stay motionless and hidden and are camouflaged and nearly odorless. They do this to avoid attracting the attention of predators. The mothers return to nurse them several times a day. While they may appear abandoned, they are not abandoned. Their mother is nearby and will not return while you are present. This is true even if the baby looks hungry or appears to beg from you.

The best thing you can do to help these fawns is to move quickly and quietly away from them. If people capture these fawns and bring them in for rehabilitation, for every fawn that is truly orphaned there will be many, many more perfectly healthy fawns that people will be kidnapping from their mother. Additionally, fawns cannot be legally rehabilitated in Vermont.

White-tailed Deer Habitat

How many deer can Vermont’s habitat support?

Estimating the maximum number of animals an environment can support long-term, often called ecological or biological carrying capacity, requires an enormous amount of time and monetary resources. Additionally, it changes over time based on weather conditions, abundance of mast crops, changes in forest structure and composition, and other factors. As a result, substantial resources would be expended to obtain an estimate that would very quickly be outdated and potentially inaccurate. Fortunately, research on the impact deer have on forest ecosystems is extensive and shows some general patterns. In most cases, long-term deer densities exceeding 20 deer per square mile are capable of altering forest plant communities, threatening endangered plant species, reducing ground-level hiding cover and forage for other wildlife species and reducing abundance of nesting birds (McShea and Rappole 2000, McGraw and Furedi 2005, Côté et al., 2006, deCalesta 1994). In some cases, negative impacts were observed at densities as low as 13 deer per square mile (deCalesta 1994, Marquis et al. 1992). In degraded habitats with limited available forage, negative impacts may occur at even lower densities.

Instead of measuring the habitat, a better approach is to monitor the physical condition of the deer themselves as an indicator of where the population is relative to carrying capacity (i.e., above or below). When deer numbers exceed what the habitat can support, each deer has access to less food or lower quality food. As a result, their physical condition (e.g., body weight, reproductive rate, antler size) begins to decline. These physical condition measurements are easily monitored from harvested or road-killed deer. Long-term trends in these measurements were used to set regional deer density objectives in the department’s 2020-2030 Big Game Management Plan. These objectives represent department biologists’ best estimates of how many deer each WMU can support over the next 10 years.

What type of habitat do deer prefer?

White-tailed deer are highly adaptable and can thrive in a variety of habitats. Optimum deer habitat is often described as a mosaic of fields and forests. These areas provide abundant forage and shelter. Conversely, large, open agricultural areas often lack sufficient shelter and large blocks of forest often have limited forage. In Vermont, deer are most abundant in valley areas with a mix of forest and field and easier winters. Deer numbers are lower in large blocks of forest, particularly those with limited young forest habitat, and at higher elevations where winters are more severe.

What is a deer wintering area, and why are they important?

Vermont is near the northern limit of white-tailed deer range. Deer regularly cope with severe winter conditions including extended periods of low temperatures, deep snow and limited mobility. Consequently, winter is often identified as the primary factor determining the size of northern deer populations, with survival primarily influenced by winter severity and the availability of winter habitat.

Deer wintering areas (DWA), or “deer yards,” are habitats that provide shelter for deer during periods of deep snow or extreme cold. These areas are often comprised of mature conifer stands (e.g., hemlock, spruce, fir, cedar, pine), which reduce snow depth, wind speeds, and radiant heat loss. Deer exhibit a great deal of fidelity to specific DWAs, usually returning to the same area each year. Functional DWAs in the northeast may comprise less than 10% of summer deer range.

What are the impacts of deer on forest habitats?

White-tailed deer play an important role in our ecosystems. However, when deer become overabundant their feeding can alter forest plant communities, threaten endangered plant species, limit regeneration of many native tree species, reduce ground-level hiding cover and forage for other wildlife species, reduce the abundance of nesting birds, and contribute to the proliferation of invasive species. Over time, this reduces the quality of forest habitats for deer and many other species, reduces the overall health of forest ecosystems, and has economic impacts for forest landowners.

How can I tell if there are too many deer in my area?

Evidence of overabundant deer isn’t always obvious to a casual observer and can sometimes be difficult even for natural resource professionals due to complicating factors like land use or forest management history, or the presence of invasive plants. However, there are a few things to look for that may indicate there are more deer than the habitat can support.

- Browse lines are perhaps the most obvious evidence of overabundant deer. Browse lines occur when deer eat most of the live vegetation within their reach, resulting in a line about 5 or 6 feet off the ground with green vegetation above and only trunks or dead stems below. These are most obvious along field edges but can also be observed in the woods.

- Heavily browsed tree seedlings may also indicate deer are overabundant, but interpretation is more complicated than it may seem. Deer prefer to browse certain species, so some (e.g., ash, sugar maple, yellow birch) may show heavy browse while others (e.g., black birch, beech) may be untouched. It is important to focus on the species deer prefer, which may not be the most common species in many forest understories today. It is also important to note that heavy browsing should be expected in deer wintering areas.

- Invasive plant-dominated understories may be related to deer abundance. As deer eat native tree seedlings and other vegetation, they facilitate the proliferation of invasive plants by helping them outcompete the natives.

- Fern-dominated understories can be a result of deer eating tree seedlings and other native vegetation that would normally compete with ferns. Past forest management practices can also be a factor in these areas.

- Deer exclosures can be helpful to demonstrate the impact deer may be having. Exclosures involve fencing deer out of a small area in the forest to prevent them from browsing. A common size is 10’ x 10’, but they can be larger or smaller. After a few years, if deer are having an impact there will be obvious differences in the vegetation inside the exclosure compared to the vegetation outside.

How can deer habitat be improved?

In Vermont, the primary factors limiting habitat quality for deer are the amount of young forest habitat (forest stands less than 20 years old) and the quality and quantity of functional wintering areas.

Young forest stands provide abundant food and cover for deer. As a result, the amount of young forest habitat, which is created by natural disturbance, forest management, or abandoned farmland reverting to forest, has a significant influence on how many deer an area can support. In most of Vermont, forests are getting older, and the amount of young forest habitat has declined and is now at very low levels in many areas. Creating more young forest habitat will improve overall habitat quality for deer and many other wildlife species.

High quality winter habitat is critical for deer to survive winters in Vermont. Regardless of the quality of summer habitat, deer numbers will be limited by quality and quantity of winter habitats. Maintaining large areas of mature evergreen trees (i.e., hemlock, cedar, spruce, fir, and pine), particularly at lower elevations, and minimizing disturbance of deer in these areas during the winter months will help more deer survive this challenging period.

For more information on habitat management for deer, check out the deer section of A Landowner’s Guide – Wildlife Habitat Management for Lands in Vermont

What resources are available for landowners looking to improve their land for wildlife?

Many resources for interested landowners are available on the department’s website.

White-tailed Deer Management

What are the department’s deer management goals?

Deer management goals established in the 2020-2030 Big Game Management Plan are:

- Maintain an abundant and healthy deer population.

- Maintain adequate quantity and quality of deer wintering areas (DWAs) to sustain regionally established population objectives.

- Maintain the deer population at levels that are socially acceptable and ecologically sustainable.

- Minimize the number of deer-human conflicts.

- Provide a quality deer hunting experience for as many hunters as possible.

How are deer density objectives determined?

WMU-specific deer density objectives in the 2020-2030 Big Game Management Plan represent department biologists’ best estimates of how many deer each WMU can support over the next 10 years, given current and projected habitat conditions. This was informed by long-term trends in deer abundance and physical condition (i.e., body weights, reproductive rates, antler size), observed impacts of deer on forest ecosystems, and scientific research on deer impacts to forests at various densities. These objectives aim to maintain deer populations at levels that are socially acceptable and ecologically sustainable.

How does the department estimate deer numbers?

The department estimates deer numbers using a series of population models. These models incorporate information like the number and age of harvested deer, hunting effort, deer sighting rates, winter severity, and trends in the number of road-killed deer. These models are continually improved by incorporating new or updated data and scientific research findings, and they provide reasonably accurate population estimates.

How does the department determine if deer numbers should be increased or decreased?

In a given year, this determination is based on how the estimated deer population in a WMU compares to the population objective for that WMU established in the 2020-2030 Big Game Management Plan. If the estimate is close to the objective, the department will attempt to stabilize deer numbers at that level. If the estimate is substantially above the objective, the department will attempt to reduce the population. Conversely, if the estimate is substantially below the objective the population will be allowed to increase.

The department’s overarching goal is to maintain a healthy and sustainable deer population. If the physical condition of deer (e.g., body weight, birth rate, antler size) is declining, or below optimal levels, that indicates the population has exceeded the level that the habitat can support. Population objectives for each WMU are set at levels that department biologists believe should be sustainable given current habitat conditions.

How does the department determine how many antlerless permits to allocate each year?

Deer populations are managed by adjusting the mortality rate of adult does – that is, the percentage of the doe population that dies each year from all causes. Long-term monitoring in Vermont indicates that, on average, 21 percent of adult does (1+ year old) must die each year to keep the deer population stable. Therefore, a higher mortality rate will cause the population to decline, and a lower mortality rate will cause it to increase.

To determine how many does must be taken by hunters to achieve the desired mortality rate and management action (increase, stabilize, or decrease), department biologists first account for non-hunting mortality. Non-hunting mortality includes all causes other than hunting and can be reliably estimated from age structure data. It varies from year to year and among WMUs, with that variation mostly related to winter severity. In WMUs where winters are most severe, non-hunting mortality may be sufficient to prevent or strongly limit population growth, and little or no doe harvest may be necessary. Conversely, in areas with relatively easy winters hunting may need to account for most doe mortality.

With these factors considered, and a target doe harvest determined, biologists then account for the expected doe harvest during the archery and youth/novice seasons. The remaining harvest must be achieved with muzzleloader antlerless permits, and the number of permits required to achieve that harvest is determined based on average fill rates for those permits in recent years. For example, a 20 percent fill rate means that it takes five permits to harvest one antlerless deer.

How are wounding rates accounted for in management decisions?

Wounding is, unfortunately, an unavoidable part of hunting. No matter how much a hunter practices or is selective about the shots they take, deflected arrows, jumped strings, buck fever, and other factors are, for the most part, out of our control. It is important to note that wounding rate (i.e., the proportion of deer hunters shoot, but do not recover) is not the same as wounding loss (i.e., the proportion of deer hunter shoot, but are not recovered and actually die). The department is most interested in wounding loss.

The department uses a non-reporting rate of 10% to account for deer that are killed by hunters and not recovered, and deer that are otherwise legally harvested but not reported (typically a lost report or other error by the reporting station). This means that for every 10 deer that are reported, one additional deer is assumed to have been killed but not accounted for. This rate is based on scientific research on wounding loss during various hunting seasons and department data on harvest reporting rates in Vermont.

How are poaching, predation, and other non-hunting mortality accounted for?

Biologists and managers are more interested in total annual mortality (i.e., what percentage of animals die each year), than each individual cause of mortality. Total mortality is relatively easy to measure or estimate from age structure data and can then be easily divided into hunting and non-hunting causes. It is very difficult to determine how much of that non-hunting mortality is from predation or any other single cause (e.g., roadkill, starvation, disease, poaching, etc.), and that detail isn’t necessary to manage populations.

For deer, research has shown that about half of fawns will die during the first couple months of their life. This is true in areas with or without predators. The difference is whether most of them die of starvation or predation. In other words, fawn predation is compensatory – that is, it does not add to total mortality but instead replaces other causes. Recent research is finding that this is also true of coyote predation on adult deer, particularly during the winter. Predation increases during severe winters, when deep snow limits deer movement, but it has essentially replaced starvation as the primary cause of death. In mild winters, predation of adult deer is minimal. In the end, the non-hunting portion of mortality (from predation and all other causes) in Vermont is strongly related to winter severity and can therefore be accounted for in management decisions. To be clear, predators can occasionally impact local deer herds, but they do not limit deer populations at larger scales like a wildlife management unit.

White-tailed Deer Hunting

Tags, Limits and Seasons

Do I need to buy a separate deer tag or does it come with my hunting license?

A buck tag comes with every hunting license sold in Vermont (except for the nonresident smallgame license). It is good for one legal buck harvested during the 16-day regular November deer season. Only one deer per hunter may be harvested during the 16-day regular November season—a legal buck. Other deer require separate tags for either archery or muzzleloader seasons.

How many deer can I harvest in a calendar year?

You can harvest 4 deer per year, of which only one may be a legal buck. You must purchase a new tag for each deer. Youth and novice hunters can take two legal bucks, provided that one is taken during the youth or novice season, not to exceed the annual limit of four deer.

When can I take an antlerless deer?

Antlerless deer can only be killed during archery season and during muzzleloader season if a hunter drew an antlerless muzzleloader permit.

How many deer may be taken in archery season?

One legal buck may be taken in archery deer season. Each year, a decision is made in June on whether or not antlerless deer may also be taken in some or all of the Wildlife Management Units (WMUs). The total number could be as many as four deer taken in archery season if you don’t shoot any deer in the other deer seasons.

Can I take all four deer of the annual limit in the archery deer season?

You can purchase four archery licenses with tags and take all four deer for the year in the archery deer season. Only one of these deer may be a legal buck.

What is considered a legal buck?

In Wildlife Management Units C, D1, D2 E1, E2, G, I, L, M, P, and Q a legal buck shall be any deer with at least one antler three inches or more in length.

In Wildlife Management Units A, B, F1, F2, H, J1, J2, K, N, and O a legal buck shall be any deer with at least one antler with two or more antler points one inch in length or longer. A point is an antler projection of at least one inch measured from base to tip.

Can I shoot a spikehorn during archery season, rifle season, or muzzleloader season?

Yes, in Wildlife Management Units C, D1, D2 E1, E2, G, I, L, M, P, and Q where a legal buck is any deer with at least one antler three inches or more in length. Spikehorns are also legal for youth hunters 15 years or younger and novice hunters to harvest on youth and novice weekend.

Why are youth hunters allowed to shoot any deer?

Youth harvest of any deer does not keep us from achieving our goals set out in the antler restriction regulation or the annual antlerless harvest objectives. Youth harvest represents a small percentage of overall annual harvest, and spikehorns and antlerless deer represent a small part of this harvest. We also want them to take these deer that are otherwise not sampled in the harvest during other seasons for research and management purposes. We need data on yearling bucks and fawns comparable to data collected since the 1940s that are used to track the health of the deer herd.

Can I use my muzzleloader during archery season?

The muzzleloader season and the archery season are separate seasons with separate sets of regulations that just happen to run at the same time. If you are muzzleloader hunting, you must have a muzzleloader license, follow muzzleloader regulations, and only harvest a legal buck unless you have won an antlerless permit. If you are archery hunting, you must have archery tags, follow archery regulations, and can harvest a legal buck or antlerless deer, depending on your WMU.

If I don’t shoot a buck during the early part of archery deer season, can I use my bow or crossbow to take a buck during the 16-day regular November deer season, and if I can, which tag do I use?

Yes. You may shoot a buck during the 16-day regular November deer season with your bow or crossbow, but you must tag that buck with your buck tag from your hunting or combination hunting and fishing license -- NOT your archery license tag.

Am I restricted to only using a rifle during the 16-day regular November deer season?

No. During the 16-day regular November deer season, you may use a centerfire rifle, a muzzleloader rifle or shotgun, a bow and arrow, a crossbow, or a pistol. BUT, the only tag you may use during this season is the “Buck Tag” on your hunting or combination hunting and fishing license.

When is the muzzleloader deer season?

The basic muzzleloader deer season is for nine consecutive days beginning the first Saturday after the end of the 16-day regular November season. A legal buck may be taken if the hunter did not take one earlier in the same year in the other deer seasons. An antlerless deer may be taken during this season in a designated WMU if the Fish and Wildlife Board approves the issuing of anterless permits, and the hunter has an antlerless permit and has not already taken four deer.

There is an early four-day muzzleloader deer season?

The Fish and Wildlife Board decides annually if this season will be held. If approved by the Board, an early muzzleloader season only for antlerless deer will be a hunting opportunity if the hunter has an antlerless permit for a designated WMU and has not already taken four deer.

Are there ever leftover antlerless permits I can get after the lottery is over?

Yes, these are available on a first come, first served basis on the department website shortly after the lottery results are announced.

Can I hunt deer on my own land without a license?

Yes, landowners, their spouse and minor children can hunt, fish and trap on their own land without a license, except on youth deer and turkey weekends, when young hunters need a youth license. You must follow all regulations and hunt within season. You must also create your own tag to make it legal to transport to the weigh station. A non-resident owner of land has equal privilege if his or her land is NOT posted.

Can I hunt on my own land without a license if my license has been suspended?

No, a person who is under suspension for the right to hunt, fish and trap may not hunt, fish or trap on their own property during the period of suspension.

Baiting and Lures

Can I use scents and lures for deer hunting?

Yes, artificial scents and lures are legal for deer hunting, provided they are not designed to be consumed by eating or licking. It is illegal to use natural urine-based lures. Lures containing natural deer urine or other bodily fluids increase the risk of chronic wasting disease being introduced to Vermont’s deer herd.

Can I bait deer?

No, it is illegal to bait or feed deer in Vermont.

Why are food plots not considered baiting?

Feeding and baiting of deer are illegal in Vermont primarily because of the increased disease transmission risk associated with these practices. Food plots do not increase disease transmission risk.

Food plots are available at all times of day during the normal growing season, often well outside of the hunting seasons. Food plots also benefit many wildlife species, including small mammals, songbirds, and pollinators, not just deer or other game species. Additionally, it is very difficult to make a distinction between food plots, agricultural crops, apple orchards, timber harvests, or other habitat management. All can improve habitat quality and attract deer or other wildlife.

Place to Hunt and Posting

How can I find a place to hunt?

There are thousands of acres of public lands distributed widely across Vermont. Most of these lands are open to hunting, fishing, and other forms of wildlife-based recreation. Visit vtfishandwildlife.com/hunt/find-a-place-to-hunt for more information.

Hunting on private land is also an option in Vermont, and more than 80% of deer habitat is on private land. Landowner permission is not required for hunting on private land in Vermont, except on land legally posted with signs prohibiting hunting. However, the department strongly encourages hunters to always seek permission from landowners. The privilege of using private land is extended by generous landowners, and most landowners in Vermont allow hunting when asked.

Do I need permission to hunt on private land?

By law, landowner permission is not required for hunting on private land in Vermont, except on land legally posted with signs prohibiting hunting. However, the department strongly encourages hunters to always seek permission from landowners. The privilege of using private land is extended by generous landowners, and most landowners allow hunting when asked. Regardless of whether the land is posted or not, a hunter must show their license and must leave the land immediately on demand if requested by a landowner.

Landowners who permit you to hunt on their land are doing you a favor and placing their trust in you. Building and maintaining landowner relationships is an important part of hunting.

Why are landowners enrolled in Use Value allowed to post their land?

The Use Value Appraisal (UVA) program (also called “Current Use” or “Land Use”) is designed to help maintain Vermont’s working landscape and limit development of that land. Enrolled land is appraised for property taxes based on its value for forestry or agriculture, rather than its fair market (development) value. The program is designed to maintain open, working lands (forests and farms) and to protect those lands from development to benefit both healthy forests and wildlife habitat. It does not have a recreation or public access component, and, therefore, private landowners enrolled in this program still have the right to legally post their property.

Several other states’ versions of the UVA program have a tiered system, whereby landowners who keep their land open to recreation receive a larger property tax reduction than those who choose to post their land. The structure of our program is set in state statute, and although the department has previously proposed a similar tiered approach in Vermont, it has not been supported by the Legislature.

Can the department do something to encourage landowners not to post their land?

The best tool currently available to the department is to give landowners of 25 contiguous acres or more, who do not post their land, first priority in receiving a muzzleloader antlerless permit in the WMU their land is in.

The department has previously proposed a tiered approach to the UVA program, whereby landowners who keep their land open to recreation receive a larger property tax reduction than those who choose to post their land. The structure of our program is set in state stature, and this change has not been supported by the Legislature.

The department will continue to pursue options to encourage landowners to keep their land open for hunting and other forms of outdoor recreation. The department also encourages landowners that do choose to post their land to use Hunting by Permission Only signs instead of traditional Posted signs. It is important to note that most landowners that post only wish to know who is on their property and will allow hunting if asked nicely.

After the Harvest

Can I use a dog to help find my deer?

A hunter who believes they have legally killed or wounded a deer during hunting season may engage a person who has a “Leashed Tracking Dog Certificate” issued by the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department to track and recover the animal during the season or within 24 hours after the season ends.

Do I need to be in the vehicle while transporting my harvested deer to a weigh station?

Yes, the person who harvested the deer must be with the carcass while being transported.

Where can I report my harvested deer?

Vermont hunters who take deer must report them within 48-hours by bringing them to a big game reporting station (or by reporting it online if that option is available).

How do I find a meat cutter to process my deer?

You had a successful hunt. Now what. Check out these videos to learn how to get your deer from field to table.

If processing the deer yourself is not an option see the list of wild game processors below.

Can I bring a deer carcass into Vermont if I went hunting out of state?

It is illegal to import or possess legally taken deer or elk, or parts of deer or elk, from states and Canadian provinces that have, or have had Chronic Wasting Disease, or from any captive hunt or farm facilities, regardless of its disease history, with the following exceptions:

- Meat that is boneless.

- Hides or capes with no part of the head attached.

- Clean skull-cap with antlers attached.

- Antlers with no other meat or tissue attached.

- Finished taxidermy heads.

- Upper canine teeth with no tissue attached.

- For a list of states and provinces with CWD, click here

Hunter Ed, Mentors and Hunters' Impact

How do I find a hunter education course?

Visit vtfishandwildlife.com/hunt/hunter-education to find a course or other information on the department’s Hunter Education program.

I’m new to hunting. How do I find a mentor?

There are lots of ways to find a hunting mentor but remember: hunting mentors are people who know how to hunt. They are people – be respectful of their time and be open to their ideas.

- Attend a Learn to Hunt program – the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department hosts at least two Learn to Hunt (LTH) seminars each year. One is held in the spring for turkey season, and the other in the fall for deer season. These seminars are for new adult hunters and cover hunting tactics, game processing, and laws, but also pair new hunters with experienced hunting mentors. For more information about the LTH programs, e-mail Nicole.Meier@vermont.gov

- Attend a seminar – when hunting seasons are coming up, consider attending a hunting seminar hosted by the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. Most seminars are conducted by volunteer hunter education instructors, and while they can teach you about hunting, you might also meet a mentor there. Click here for a list of seminars coming up.

- Join a club – fish and game clubs have a rich history in Vermont, and they are a great place to practice shooting and meet other hunters. Visit the Vermont Federation of Sportsman’s Clubs website for a list of clubs. Other organizations like the Vermont Chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation and New England Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers are great places to join to meet experienced and new hunters alike.

If you do find a hunting mentor, there is a chance it will be an enduring friendship and a bond like no other. There is a lifetime of learning and enjoyment to be found in the woods; consider sharing your passion with someone new. If you are interested in becoming a certified hunting mentor, contact Nicole.Meier@vermont.gov

Do hunters help the economy in Vermont?

Hunters spend more than $292 million in Vermont annually according to the latest survey (2011) by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Hunters and anglers are important to Vermont’s economy because they spend a lot of money, and because of the timing and distribution of that money. High points in hunting and fishing activity tend to occur when other recreational activities are in transition. Hunters make their purchases throughout the state, including in our most rural areas.

White-tailed Deer Conflicts

What role do deer play in the transmission of Lyme disease?

Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi. Larval and nymphal black-legged ticks (Lxodes scapularis; also known as deer ticks) are infected when they feed on small mammals, such as white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), carrying the bacterium. The ticks can then transmit the bacterium if they later feed on a human. White-tailed deer are the primary reproductive host of the adult black-legged tick, so they may influence the abundance of ticks on the landscape. However, deer are not a competent reservoir for the Lyme disease bacterium (i.e., ticks cannot become infected with the bacterium by feeding on deer). Areas with high deer density often have more ticks, but tick abundance is also influenced by habitat conditions and the abundance of other mammals that ticks may feed on. The relationship between deer populations and Lyme disease incidence is complex and still unclear.

How can I keep deer from eating my garden or landscape plants?

There are many options for deterring deer from your yard, and some are more effective than others.

- Tall fencing (8 feet or more) is the most effective option but can also be expensive and unsightly. Shorter fencing can work for smaller areas, as deer will be hesitant to jump into a confined space.

- Scents or sprays may deter deer for short periods of time. These products add an undesirable smell or taste to plants, but need to be reapplied regularly, including after every rain event.

- Loud, startling noises can scare deer away from an area, and there are commercially available motion-activated noisemakers designed for this purpose. However, as with most scare tactics, deer may eventually learn that the noise is not a threat simply ignore it.

- Hunt the deer to remove the problem. Legal hunting helps limit deer populations so there is less need for them to come into your yard in search of food. It also provides a legitimate threat that they will avoid, or that will make other deterrents more effective.

Ultimately, deer are very resourceful and adaptable to different conditions, so there is no guarantee any one method of deterrent will work alone. Combining different methods to catch deer off guard will increase your chance of success.

Vermont's Deer Herd Health

What is Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)?

Chronic Wasting Disease, or CWD, is a neurological (brain and nervous system) disease found in some deer, elk, and moose. Most cases of CWD occur in adult animals. The disease is progressive and always fatal. The most obvious and consistent clinical sign of CWD is weight loss over time. Behavioral changes also occur in the majority of cases, including decreased interactions with other animals, listlessness, lowering of the head, blank facial expression, repetitive walking in set patterns, and a smell like meat starting to rot.

It is not known exactly how CWD is spread. It is believed that the agent responsible for the disease may be spread both directly (animal to animal contact) and indirectly (soil or other surface to animal). It is thought that the most common mode of transmission from an infected animal is via saliva, urine and feces.

Check out our Chronic Wasting Disease webpage for more info