Ecology and Physical Setting

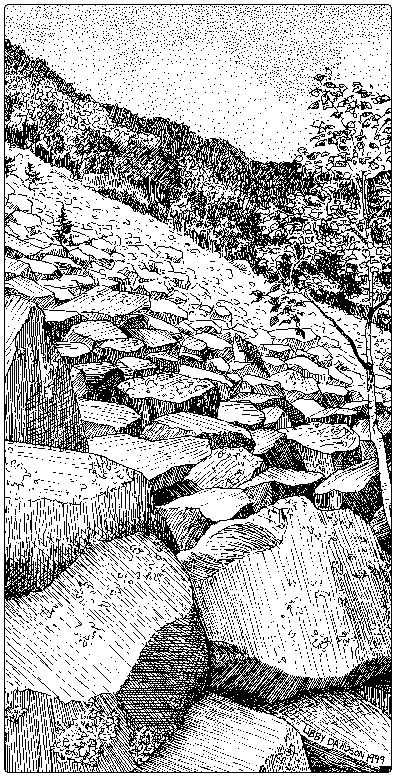

Open Talus is the accumulation of rockfall below cliffs. It can occur on any rock type, from limestone to shale to schist to granite. The largest Open Talus areas occur either where the rock is so unstable that it prevents the establishment of trees, as on shale talus, or where the structure of the rock causes it to break into large, angular blocks where soil cannot accumulate, as on granite, quartzite, or gneiss talus. Once large blocks are in place, they may be quite stable, but vegetation cannot become established because there is no soil—any soil that develops is far beneath the surface in deep fissures.

In areas of soft, easily weathered rock like limestone, the rock fragments tend to be small, soil develops relatively quickly, and plants can easily get established. In these places, Open Talus is rare—most limestone talus supports some trees and is therefore considered woodland.

In Open Talus that is made from quartzite, gneiss, or granite, the spaces between the rocks are large and can form deep caverns. These deep spaces have some curious properties. They can be so well insulated from outside temperatures that they are cool in summer and warm in winter. Like true caves, their temperature remains relatively constant—in the range of 43-48˚F—throughout the year. These temperature-moderated places are the perfect habitat for certain snakes that need stable temperatures to overwinter.

At the surface, however, temperatures on a talus slope can be extreme. The open rock can absorb a lot of heat on a sunny summer day, and the result is a dry, scorching environment.

Vegetation

Soil is often a sparse commodity in Open Talus. Where talus is formed by large blocks, soil may accumulate so far beneath the jumble of rocks that no light can reach it. In this case, it will support no green plants. The only visible vegetation in the talus may be lichens and mosses growing on the surface of the rocks.

Where talus is formed by schist or shale, however, the rocks are usually tightly packed and the spaces between them can hold some soil. With adequate soil, a few small, poorly formed trees grow from between rocks, and herbaceous plants grow among them or in mossy places on the rocks. Rock chemistry and climate are important factors in determining what species are present. Shale Talus can vary from strongly acidic to moderately calcareous. The cold, high elevation Boreal Calcareous Talus beneath the cliffs at Smugglers Notch and Lake Willoughby has perhaps the most distinct flora. The talus shares many of the rare and uncommon species associated with Boreal Calcareous Cliffs.

Wildlife Habitat

Open talus provides important winter hibernation habitat for many species, especially snakes. Deep within talus slopes, the open spaces between rocks are moderated from the exterior cold winter temperatures and protect cold-blooded reptiles from freezing. The location and setting of an Open Talus is important in determining which species will use it. The rare timber rattlesnake, eastern ratsnake, and five-lined skink use talus slopes near the temperate oak and pine forests where they spend their summers. Eastern ribbonsnakes sometimes congregate and overwinter in talus slopes that are near water or wetlands, their primary summer habitat. DeKay’s brownsnake and common gartersnake are much more widely distributed across Vermont and will use any talus slopes with adequate deep cavities. Eastern small-footed bats hibernate in caves but use south-facing, sun-warmed Open Talus for summer roosting. Rock voles are rare in Vermont and are found in cool, mossy, rocky, coniferous woods. They use talus slopes near streams as denning sites.

Variants

- Shale Talus is made from smaller, flatter rock fragments. Shale Talus is inherently less stable than Open Talus made from large rock fragments, and this difference, along with the differences in the size of the rock fragments and the chemical nature of the rock, correlates with differences in soils and vegetation. The shale, slate, schist and other platy rocks that form this community are usually acidic to moderately calcareous. More strongly calcareous talus at low elevations tends to support tree growth and is better classified as Oak-Maple Limestone Talus Woodland.

-

Eastern timber rattlesnake is a rare inhabitant of

Open Talus.Boreal Calcareous Talus is found below Boreal Calcareous Cliffs. Good examples are found in Smugglers Notch and above Lake Willoughby. The talus comprises rock fragments of all sizes, from small platy fragments to immense boulders. Seepage from cliffs above can form small, moisture-rich pockets in the talus. Rockfall and landslides, as well as ice fall and snow avalanches, are frequent disturbances. Remarkably, many rare plants can persist in this dynamic and unstable environment.

Related Communities

- Cold Air Talus is a rare community that occurs where cold temperatures persist at the bases of talus slopes. Here black spruce, Labrador tea, and other northern or high elevation plants can be found outside of their normal ranges.

- Boreal Talus Woodland, Northern Hardwood Talus Woodland, Oak-Black Birch Talus Woodland, and Oak-Maple Limestone Talus Woodland all have canopy cover greater than 25 percent and may be adjacent to Open Talus.

Conservation Status and Management Considerations

Several high-quality examples of Open Talus are protected on conservation lands. Visitors should use extreme care when visiting Open Talus communities, as they are steep and difficult to climb, and may have deep crevices between boulders. A misplaced step could be disastrous. Shale Talus and Boreal Calcareous Talus are inherently unstable and difficult to climb. Ascending these can uproot any plants that have taken hold there.

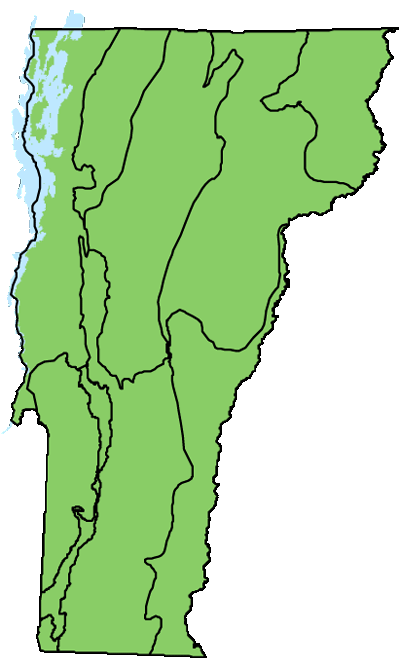

Distribution/Abundance

Open Talus is rare in Vermont but can be found in every biophysical region. Most examples are small. Open talus communities can be found throughout the Northeast.

Associated Animals

DeKay’s brownsnake – Storeria dekayi

Common gartersnake – Thamnophis sirtalis

Rare and Uncommon Animals

Common five-lined skink – Plestiodon fasciatus

Eastern ratsnake – Pantherophis alleghaniensis

Timber rattlesnake – Crotalus horridus

Eastern ribbonsnake – Thamnophis sauritus

Rock vole – Microtus chrotorrhinus

Eastern small-footed bat – Myotis leibii

Places to Visit

Bristol Cliffs, Bristol, Green Mountain National Forest (GMNF)

Birdseye Wildlife Management Area, Ira and Poultney, Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department

Smugglers Notch, Jeffersonville, Mount Mansfield State Forest, Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation

White Rocks, Wallingford, White Rocks National Recreation Area, GMNF