Ecology and Physical Setting

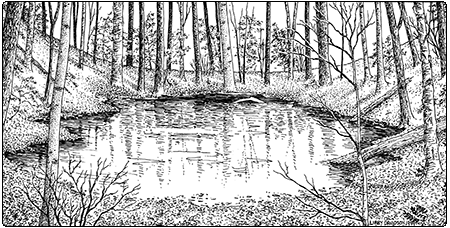

In spring, the loud, duck-like quacking of wood frogs makes Vernal Pools hard to miss, even from a distance, but in the summer, one can walk obliviously past a dry pool. These small, temporary bodies of water occur in forest depressions, and are underlain by a relatively impermeable layer, such as bedrock or hardpan. Runoff from melting snow and spring rains fills these pools with water. This water, which persists into early summer, is usually less than four feet deep. The pools typically dry up by late summer, but may fill again with fall rains. Vernal Pools generally lack inlet and outlet streams, although water may flow out during especially heavy rains or rapid snow melt. Most Vernal Pools are smaller than 5,000 square feet, and all have very small watersheds.

Vernal Pools have a rich, organic surface layer of soil, resulting from the long duration of standing water in the spring and fall. This hydrologic regime is also responsible for the general paucity of vegetation in the parts of Vernal Pools that are regularly inundated. The seasonal pattern of inundation and drying is what makes them such critical habitat for the characteristic amphibians and invertebrates that define this natural community.

Vernal Pools may be difficult to identify after water levels have receded. However, the cup-shaped basin, the general lack of vegetation, the presence of relatively thick organic soil layers compared to surrounding forests, and the water stains left on leaves and the forest floor can reveal the locations of these ephemeral pools.

Vernal Pools may be difficult to identify after water levels have receded. However, the cup-shaped basin, the general lack of vegetation, the presence of relatively thick organic soil layers compared to surrounding forests, and the water stains left on leaves and the forest floor can reveal the locations of these ephemeral pools.

Vegetation

Vernal Pools generally have very little vegetation as a result of the long periods of inundation. Wetland plants may occur as scattered individuals or a narrow fringe around the margin of the pool’s high-water line. In some pools, annual plants—whose seeds have been dormant in the soil—become established after water recedes. Typical wetland species associated with Vernal Pools include sensitive fern, marsh fern, rice cutgrass, northern bugleweed, hop sedge, and mad-dog skullcap.

The upland forests surrounding Vernal Pools are critical to their ecological integrity. Most pools are small enough that the canopy of adjacent upland forests keeps the pools shaded. The results are cooler water temperature and less evaporation, which mean that the pools will persist later into the spring or summer.

Wildlife Habitat

Unlike most natural communities that are largely characterized by their flora, Vernal Pools are characterized by their fauna. Vernal Pools are best known as amphibian breeding habitat. Amphibians that require vernal pool conditions for breeding in Vermont include wood frog, spotted salamander, Jefferson salamander, and blue-spotted salamander. Spring peepers, though they don’t require Vernal Pools, may breed there. These species all migrate from surrounding forests to Vernal Pools to mate and lay eggs in early spring. Spotted salamanders are one of the earliest species to emerge and migrate, with hundreds of individuals moving toward a well-used pool on the first warm rainy night in March or April, sometimes crawling over remaining snow to reach a breeding pool. Frog tadpoles and salamander larvae that hatch from the eggs must develop quickly in their race against the approaching summer heat that will evaporate the water in their pool.

As the young amphibians mature, they feed on algae and some of the rich and diverse invertebrate fauna found in the temporary pools. Invertebrates likely make up the majority of species and animal biomass in Vernal Pools. Some of the characteristic invertebrates include knob-lipped fairy shrimp, fingernail clams, amphibious snails, caddisfly larvae, water fleas, and copepods, but there are many more. These small animals have all developed strategies to survive the seasons of the year when the pool is dry. Some species disperse to other habitats, while others lay eggs and die or go into resting stages that are tolerant of both drought and freezing conditions.

As the season progresses and the pool dries out, the amphibians move into the surrounding forest, where they spend most of their adult lives. This surrounding forest is critical to pool-breeding amphibians. The frogs and salamanders may travel up to 1,000 feet away, finding moisture, shade, and food in burrows and under fallen logs. Regardless of forest type, amphibians need a closed forest canopy, abundant downed wood, and thick duff soils.

An important characteristic of Vernal Pools is the lack of fish. Fish cannot tolerate the seasonal drying of the pools. Fish can be significant predators on amphibian eggs and larvae that are hatched in pools, ponds, and wetlands with permanent surface water.

The amphibians and their eggs in Vernal Pools can provide an important source of food to other animals, including barred owls, great blue herons, migrating solitary sandpipers, minks, and raccoons. When amphibians disperse to the uplands, they become an abundant food source for many other birds and mammals as well.

Vernal Pool conditions can be found in other types of wetlands, including forested swamps, shrub swamps, and marshes. Even amphibians that are strongly associated with Vernal Pools can breed in these habitats.

Related Communities

- Basin Shrub Swamps are distinguished by the dominance of shrubs, such as winterberry holly, highbush blueberry, or buttonbush, across nearly the entire basin. They can occur in very small, isolated depressions, and sometimes have seasonal areas of open water that can support breeding amphibians.

Conservation Status and Management Considerations

Vernal Pools are well-recognized for their importance as natural communities and as amphibian breeding habitat. Although they are widespread and numerous, and many are protected on public lands, many more remain to be found and protected. Many towns and non-profit organizations lead community efforts to locate Vernal Pools. Private landowners play an important role in protecting the thousands of Vernal Pools scattered around the state.

Vernal Pools and the animal species that depend on them are threatened by activities that alter the hydrology and substrate of individual pools, as well as by significant alteration of the surrounding forest. Multiple studies indicate that 95 percent of the salamander population using a particular breeding pool would be protected by a forested buffer that extended 500 to 600 feet into the surrounding upland habitat (Semlitsch 1998; Faccio 2003). Semlitsch termed this the salamander “life zone.” Wood frogs travel much greater distances. Road construction and development within the life zone fragments the habitat, hinders movement, and causes mortality. Logging in the immediate vicinity of Vernal Pools can also have significant effects, including direct alteration of the pool depression, changes in the amount of sunlight, leaf fall, and coarse woody debris in the pool, and the creation of deep ruts that disrupt amphibian migration. Even during periods when the pool is dry, alteration of the pool substrate may affect its ability to hold water and disturb the eggs and other drought-resistant stages of invertebrate life that form the base of the Vernal Pool food chain.

In general, it is recommended that there be no activity within the Vernal Pool depression or the adjacent 100 feet. From 100 feet to a distance of 650 feet there should be no permanent roads or development. Any timber harvesting should maintain at least 60 percent canopy cover to maintain shade, and should be conducted only when the ground is frozen and covered with snow. Some downed wood should be left in place to provide moist habitat.

Distribution/Abundance

Vernal Pools are found throughout Vermont and the Northeast. Although thousands have been identified in the state, collectively they add up to a very small total acreage

Characteristic Plants

Shrubs

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

Winterberry holly – Ilex verticillata

Herbs

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

Sensitive fern – Onoclea sensibilis

Marsh fern – Thelypteris palustris

Rice cutgrass – Leersia oryzoides

Northern bugleweed – Lycopus uniflora

Mad-dog skullcap – Scutellaria lateriflora

Nodding bur marigold – Bidens cernua

Tuckerman’s sedge – Carex tuckermanii

Hop sedge – Carex lupulina

Rare and Uncommon Plants

Floating mannagrass – Glyceria septentrionalis

Black gum – Nyssa sylvatica

Associated Animals

Wood frog – Lithobates sylvaticus

Spring peeper – Pseudacris crucifer

Spotted salamander – Ambystoma maculatum

Raccoon – Procyon lotor

Mink – Neovison vison

Star-nosed mole – Condylura cristata

Black bear – Ursus americanus

Barred owl – Strix varia

Great blue heron – Ardea herodias

Solitary sandpiper – Tringa solitaria

Emerald spreadwing – Lestes dryas

Common green darner – Anax junius

Knob-lipped fairy shrimp – Eubranchipus bundyi

Rare and Uncommon Animals

Jefferson salamander – Ambystoma jeffersonianum

Blue-spotted salamander – Ambystoma laterale

Four-toed salamander – Hemidactylium scutatum

Northern long-eared bat – Myotis septentrionalis

Places to Visit

Hubbard Park, Montpelier, Montpelier Parks Department

Red Rocks Park, South Burlington, South Burlington Recreation and Parks

Vernal Pools are scattered throughout the state. We encourage readers to locate pools in their areas.