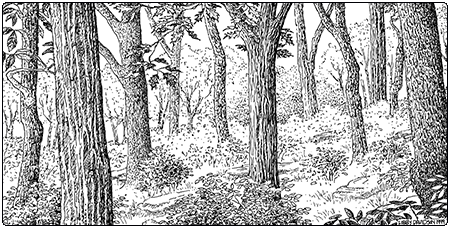

Ecology and Physical Setting

With their abundant heath shrubs and southern oaks, Dry Oak Forests provide a welcome break from the ordinary when they are encountered after a hike up a hill in Vermont’s warmer regions. They can occur both as small patches, such as on a hilltop, or as larger patches sprawling across several hundred acres of rocky terrain. They are found at low elevations, mostly on acidic bedrock.

In Dry Oak Forests, bedrock is close to the surface, and nutrients are limited. The low rainfall and warmer climate in the biophysical regions where this community occurs, along with the low moisture-holding capacity of the soils, makes these relatively dry places. Water availability varies depending on the site. Flats tend to hold more moisture, supporting better tree growth, whereas ridgetops are usually very dry, limiting tree growth. Fire may play a role in some examples of this community. Gypsy moths can affect these forests, as they thrive on oak.

Vegetation

Overall diversity in Dry Oak Forests is low. Red oak and white oak are mixed in the canopy, and chestnut oak is occasional to abundant. Black oak occurs in this community in extreme southwestern Vermont, as well as in the lower Connecticut River valley. White pine is often present, but in low abundance. Trees range from tall and massive to short and poorly formed, but the canopy is nearly continuous. Tree form is tied to soil moisture: moister sites have taller, larger diameter trees, while drier sites can have scraggly, stunted trees.

Huckleberries and blueberries form dense thickets in the understory—walking through these thickets can be difficult but is rewarding during berry season. Herbs are sparse, but the occasional flowering wood lily, downy false foxglove, or four-leaved milkweed adds color to the forest floor.

Prior to the early 20th century, these forests would likely have also supported American chestnut. Some forests may have even been dominated by chestnut—the large-diameter, tall trees would have been an impressive sight. Today, because of the non-native chestnut blight fungus, mature chestnuts are almost entirely gone from Vermont’s forests, though they persist as saplings. The rot-resistant stumps and logs are the only indicators of this species’ former glory.

Wildlife Habitat

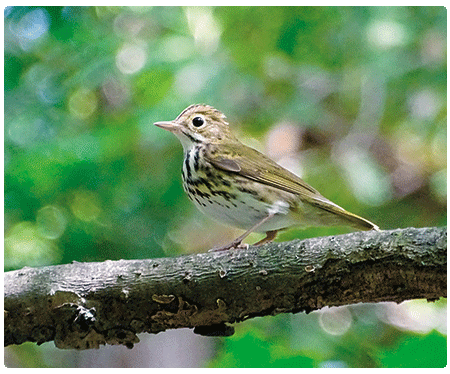

Dry Oak Forests provide abundant food for wildlife. Black bears, squirrels, chipmunks, and turkeys all rely on the calorie-rich acorns produced in the fall. During the summer, blueberries and huckleberries provide food for black bears, foxes, coyotes, and birds such as cedar waxwings. Nesting birds include eastern wood pewee, hermit thrush, scarlet tanager, and ovenbird. Two invertebrates rely on the heath family shrubs that are common in Dry Oak Forests. Blueberries and huckleberries are host plants for the uncommon brown elfin butterfly, and are some of the primary sources of pollen for the Carolina andrena bee. In the limited areas of Vermont where they occur, the rare eastern ratsnake and timber rattlesnake hunt in these forests for small mammals and birds.

Successional Trends

These oak forests are stable over time, especially on ridgetops prone to droughts. Fire may play a role in maintaining this community. For a variety of reasons, many eastern oak forests were burned by Native Americans. Researchers looking broadly at eastern oak forests (Nowacki and Abrams, 2008) have proposed that in the absence of fire, the accumulated leaf litter traps moisture and hinders oak regeneration, leading to a positive-feedback cycle of “mesophication” that ultimately results in a new community dominated by shade-tolerant, mesic-forest species. In Vermont, however, some of the best examples of Dry Oak Forest have abundant oak regeneration and no evidence of recent fire, suggesting that other processes besides fire can maintain these forests.

Related Communities

- Dry Oak-Hickory-Hophornbeam Forest has more nutrient-rich soils supporting higher diversity. Maple and hickory are mixed in with the oaks. Chestnut oak is absent from this community.

- Dry Chestnut Oak Woodland has a similar species composition, but chestnut oak is typically dominant and dry site grasses are abundant. Heath shrubs are sparse. The increased droughtiness of the soils reduces canopy cover significantly.

- Dry Red Oak-White Pine Forest shares many species but lacks the more southern species such as chestnut oak and white oak.

Conservation Status and Management Considerations

This community is somewhat uncommon in Vermont, but a few good examples are found on protected lands. A number of high quality examples are found in fragmented landscapes and are threatened by development. The use of prescribed fire may have unintended negative impacts and is not recommended.

Distribution/Abundance

Dry Oak Forest is occasionally found on acidic ridgetops in the Champlain Valley, Taconic Mountains, and Connecticut River valley. Similar communities are found more commonly to our south, where they can be widespread on ridges and other dry sites.

Characteristic Plants

Trees

Abundant Species

Red oak – Quercus rubra

White oak – Quercus alba

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

White pine – Pinus strobus

Chestnut oak – Quercus montana

Black oak – Quercus velutina

Shrubs

Abundant Species

Huckleberry – Gaylussacia baccata

Low sweet blueberry – Vaccinium angustifolium

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

Common shadbush – Amelanchier arborea

Witch hazel – Hamamelis virginiana

American chestnut – Castanea dentata

Early azalea – Rhododendron prinophyllum

Fragrant sumac – Rhus aromatica

Herbs

Abundant Species

Poverty grass – Danthonia spicata

Hairgrass – Deschampsia flexuosa

Occasional to Locally Abundant Species

Cow-wheat – Melampyrum lineare

Broad-leaved sedge – Carex platyphylla

Bottle-brush grass – Elymus hystrix

Marginal wood fern – Dryopteris marginalis

Bracken fern – Pteridium aquilinum

Panicled hawkweed – Hieracium paniculatum

Four-leaved milkweed – Asclepias quadrifolia

Rare and Uncommon Plants

Slender wheatgrass – Elymus trachycaulus

Downy arrowwood – Viburnum rafinesquianum

Panicled tick-trefoil – Desmodium paniculatum

Squawroot – Conopholis americana

Flowering dogwood – Cornus florida

Lopsided rush – Juncus secundus

Large whorled pogonia – Isotria verticillata

Sassafras – Sassafras albidum

Spotted wintergreen – Chimaphila maculata

Violet bush-clover – Lespedeza violacea

Scarlet oak – Quercus coccinea

Wood lily – Lilium philadelphicum

Smooth false-foxglove – Aureolaria flava var. flava

Rattlesnake-weed – Hieracium venosum

Fragrant sumac – Rhus aromatica

Associated Animals

Eastern chipmunk – Tamias striatus

Eastern gray squirrel – Sciurus carolinensis

Southern flying squirrel – Glaucomys volans

Black bear – Ursus americanus

Wild turkey – Meleagris gallopavo

Eastern wood pewee – Contopus virens

Wood thrush – Hylocichla mustelina

Scarlet tanager – Piranga olivacea

Ovenbird – Seiurus aurocapilla

Carolina andrena bee – Andrena carolina

Rare and Uncommon Animals

Eastern ratsnake – Pantherophis alleghaniensis

Timber rattlesnake – Crotalus horridus

Northern long-eared bat – Myotis septentrionalis

Brown elfin – Callophrys augustinus

Places to Visit

Fort Dummer State Park, Brattleboro and Guilford, Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation

Snake Mountain, Addison, Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife

North Pawlet Hills Natural Area, Pawlet, The Nature Conservancy