Protecting Vermont’s plant diversity is important because plants provide crucial habitat for most other organisms, are a food source for most animals, especially pollinators, and make our landscapes more resilient to climate change and other disturbances. Plants, in fact, are responsible for the existence of most life on earth.

Here are several factors that can cause plants to become rare.

Disappearing Habitats

Development and fragmentation of natural habitats is the most common cause for decline of plant diversity in Vermont and globally. For example, the rare Pine Oak Heath sandplain natural community found in Chittenden County is restricted to sands deposited when the glaciers retreated over 10,000 years ago. As these fragile habitats in Colchester, Essex, and Milton are developed, they no longer provide habitat for rare plants that are adapted to sandplains, or for the animals, pollinators, and fungi that depend on this natural community type.

Development and fragmentation of natural habitats is the most common cause for decline of plant diversity in Vermont and globally. For example, the rare Pine Oak Heath sandplain natural community found in Chittenden County is restricted to sands deposited when the glaciers retreated over 10,000 years ago. As these fragile habitats in Colchester, Essex, and Milton are developed, they no longer provide habitat for rare plants that are adapted to sandplains, or for the animals, pollinators, and fungi that depend on this natural community type.

Furthermore, many sandplain plant species are in decline because they are adapted to fire. Since fires no longer burn in most of this habitat, these plants are restricted to areas that mimic the effects of fire, often persisting in powerlines and field edges.

Transporting Species Around the World – Non-native and Invasive Species

Non-native species are a serious threat to Vermont’s rare flora. Over 600 plant species have been introduced to Vermont, either accidentally of purposefully, and have escaped to the wild. Although only a small proportion of these 600 species have become invasive, those species that have, can outcompete our native species and alter ecosystems.

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and Morrow’s honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii) can form impenetrable thickets, especially in the Champlain Valley, suppressing forest regeneration.

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and Morrow’s honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii) can form impenetrable thickets, especially in the Champlain Valley, suppressing forest regeneration.

Common reed (Phragmites australis), along with many other invasive plants, exude chemicals in the soil that stifle the growth of all plants around them, replacing diverse marshes and meadows with single-species stands and degrading habitat for birds and amphibians.

Common reed (Phragmites australis), along with many other invasive plants, exude chemicals in the soil that stifle the growth of all plants around them, replacing diverse marshes and meadows with single-species stands and degrading habitat for birds and amphibians.

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) covers the state’s riverbanks, increasing soil bank erosion and making Vermont’s waterways less resilient to flooding.

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) covers the state’s riverbanks, increasing soil bank erosion and making Vermont’s waterways less resilient to flooding.

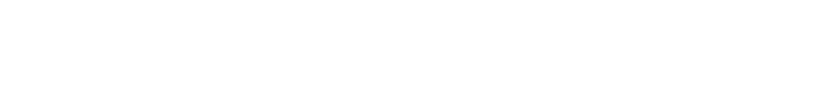

Asiatic bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) vines are pulling down the larger trees in the floodplains of the lower Connecticut River valley, resulting in a decline in the average tree age in this area.

Asiatic bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) vines are pulling down the larger trees in the floodplains of the lower Connecticut River valley, resulting in a decline in the average tree age in this area.

The costs to farmers, foresters, anglers, tourists, and ordinary Vermonters are very expensive. As a result, a number of these invasive plants are legally quarantined, which prohibits their sale or movement in the state.

Invasive animals and fungi also threaten Vermont’s native plants.

Some of the 19 species of introduced earthworm species in Vermont, particularly the crazy snake worm (Amynthas agrestis), are slowly and dramatically altering the soil and the regeneration of our forests.

Some of the 19 species of introduced earthworm species in Vermont, particularly the crazy snake worm (Amynthas agrestis), are slowly and dramatically altering the soil and the regeneration of our forests.

Many earthworm species remove the top organic soil layer and change the soil structure. This correlates with decreased plant diversity and abundance in the forest understory. Fewer native species are growing or reproducing in these altered soils, and those that are still growing may be sparser than before the earthworms arrived. The direct impacts on Vermont rare plants are still unknown.

Most of Vermont trees have an invasive insect and/or fungus that attacks them. Examples include Dutch elm disease on all elm species, chestnut blight on American chestnut, butternut canker on butternuts, beech bark disease on American beech, hemlock woolly adelgid on eastern hemlocks and gypsy moth on all oaks.

Emerald ash borer and Eurasian longhorned beetle threaten to remove ashes and maples from Vermont landscape, and oak wilt could be lethal to all Vermont’s oaks. The impact of losing these trees can have cascading effects on other coexisting life.

Emerald ash borer and Eurasian longhorned beetle threaten to remove ashes and maples from Vermont landscape, and oak wilt could be lethal to all Vermont’s oaks. The impact of losing these trees can have cascading effects on other coexisting life.

What You Can Do

- When fishing, do not release live earthworms. When gardening, do not dump horticultural products in or near the forest.

- Garden with native plants, and avoid planting exotic plants that show the potential to be aggressive. New exotic garden plants continue to be introduced to Vermont, costing land owners hundreds of dollars to control them.

- Don’t move firewood. This is the most common way that exotic insects like Emerald ash borer and oak wilt are transported.

- Become a forest pest first detector – FPFD volunteers are on the front line of defense against pest infestations by assisting with ongoing outreach, education and local planning and surveying efforts.

- Learn more at Vermont Invasives website

- Become a Plant Conservation Volunteer (PCV) and help monitor rare plants and help with habitat management.

Overharvesting

American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) was a lucrative medicinal crop to harvest from the wild during Vermont’s early settlement. Once frequent across Vermont, by the end of the 19th century, ginseng had nearly disappeared from Vermont and across its range. Though herbal alternatives to wild ginseng exist, there is increased harvest pressure on ginseng today. The department’s Natural Heritage Inventory continues to monitor ginseng as an uncommon plant that is at risk of becoming rare.

American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) was a lucrative medicinal crop to harvest from the wild during Vermont’s early settlement. Once frequent across Vermont, by the end of the 19th century, ginseng had nearly disappeared from Vermont and across its range. Though herbal alternatives to wild ginseng exist, there is increased harvest pressure on ginseng today. The department’s Natural Heritage Inventory continues to monitor ginseng as an uncommon plant that is at risk of becoming rare.

Edge of Range

Some species in Vermont are quite common in the prairies of the Midwest, or in the arctic tundra of Canada. Why should we be concerned that they are disappearing from here?

Many species vary genetically across their ranges. Plant populations on the periphery of their range are often genetically distinct from the core population, so Vermont plants may be on their way toward evolving into new species. With changing climate, many plants are on the move. If we conserve plants where they occur naturally—if we preserve their potential to adapt, migrate and evolve—they will have the best chance of successful survival in coming years, hopefully carrying with them the complex web of life they support.

- Dwarf birch (Betula minor) is known from just one Vermont location, in the alpine tundra of Mt. Mansfield. It becomes more common in northern Quebec and Labrador.

- Champlain beach grass (Ammophila breviligulata ssp. champlainensis) arrived in Vermont 10,000 to 13,000 years ago during the last ice age, when retreating glaciers allowed sea water to come up the St. Lawrence River, forming the Champlain Sea. As the region’s land rebounded from the weight of the glaciers, the salty sea water retreated and the Champlain basin gradually became an isolated body of fresh water.

Champlain beach grass continued to grow on the sand dunes of Lake Champlain. Now, isolated for millennia from coastal plants, this rare Vermont grass is evolving into its own species. Beach grass does not tolerate being flooded in the summer and the increased frequency of summer flooding is taking its toll. Record-high lake levels of 2011, reduced the number of dune grass plants in Vermont by two thirds, and the species has yet to recover.

Unique Habitat Needs

Vermont is known for its abundance of calcium-rich, limestone bedrock. This bedrock supports the rare Limestone Bluff Cedar-Pine Forest, provides Vermont’s farmlands with nutrient-rich soil, and provides habitat for numerous rare and uncommon plants.

Vermont is known for its abundance of calcium-rich, limestone bedrock. This bedrock supports the rare Limestone Bluff Cedar-Pine Forest, provides Vermont’s farmlands with nutrient-rich soil, and provides habitat for numerous rare and uncommon plants.

Many of these calcium-loving plants are rare throughout New England and restricted to areas of calcium-rich bedrock, including those associated with dry outcrops, groundwater seepage, and rich forests. These areas with rich, limy soils produce Vermont’s most dramatic displays of early spring wildflowers each year.

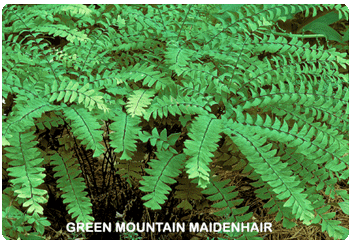

The state also contains a limited band of serpentine bedrock, a class of rock with concentrations of magnesium and iron so high that the rock and overlying soils are toxic to many species. This unusual rock harbors a uniquely adapted flora, with several species that only grow on this rock type.

Two of Vermont’s rarest plants occur only on this rock type—the Green Mountain maidenhair (Adiantum viridimontanum) and marcescent sandwort (Minuartia marcescens). The Green Mountain maidenhair was first discovered in Vermont, but was later found in Quebec and Maine as well. The marcescent sandwort is known only from the single Vermont population, and from 20 sites in far northeastern Canada.

Two of Vermont’s rarest plants occur only on this rock type—the Green Mountain maidenhair (Adiantum viridimontanum) and marcescent sandwort (Minuartia marcescens). The Green Mountain maidenhair was first discovered in Vermont, but was later found in Quebec and Maine as well. The marcescent sandwort is known only from the single Vermont population, and from 20 sites in far northeastern Canada.Extinct

The only population in the world of Robbins’s milkvetch (Astragalus robbinsii var. robbinsii) once occurred in a gorge in the Winooski River between South Burlington and Colchester. When a dam was proposed in the 1890s, there was no public outcry, and all the plants were flooded and killed. It has never been found anywhere else.