On this page find information about: Moose and Winter Ticks | Vermont's Moose Population | Vermont's Moose Hunt

Moose and Winter Ticks

What is a winter tick?

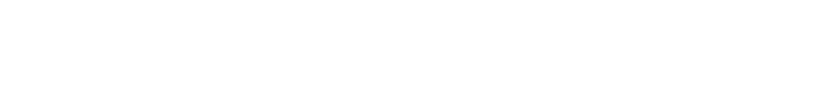

The winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus) is a species of tick that can be found across North America. They are a single-host tick, meaning they complete their entire life cycle on a single host. This is different than the ticks humans are most familiar with (black-legged ticks and American dog ticks), which drop off their host after a blood meal and infect multiple hosts over the course of their life cycle. Winter ticks find a host in the fall and spend the winter on the animal before dropping off in the spring – hence the common name, winter tick.

Unlike other ticks which have expanded their range northward, winter ticks are native to Vermont. They were recorded on moose here as early as the 1980s and were likely present here long before that.

How has climate change affected winter ticks?

Although winter ticks have been present in Vermont for decades, they are benefitting from climate change. Shorter winters benefit winter ticks in two ways.

- First, the first snowfall of the year kills most larval ticks and ends the fall questing period – the time when ticks are getting onto the moose. If that snow comes later, the larval ticks have more time to find a host, and moose will accumulate more ticks.

- Second, when the engorged adult females fall off moose in the spring, their chance of survival is lower if they land on snow instead of bare ground. As winters get shorter, winter ticks are able to thrive in areas where they were formerly limited by long winters.

How do winter ticks kill moose?

Sheer numbers. As many as 90,000 ticks have been documented on a single moose. When those ticks all take a blood meal in late winter, the moose simply cannot replace that volume of blood quick enough. This is compounded by the timing, as the moose’s energy reserves are already depleted by late winter. Even if the moose survives, they are in poor physical condition. This can affect the survival of newborn calves, which are born about a month after the ticks drop off. Further, because the moose needs to recover from this poor condition, they aren’t able to put as much energy toward growth and building energy reserves. Therefore, they enter the next winter in poorer condition which makes them more vulnerable to the impacts of winter ticks.

Do winter ticks affect moose everywhere?

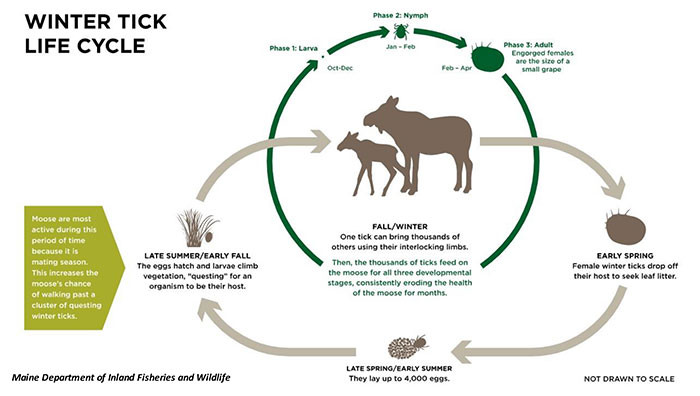

No. Winter ticks can be found on moose throughout New England and much of the southern portion of their range, but they only reach problematic levels in areas with high moose densities. Winter ticks are a host density dependent parasite and thrive during times of elevated host densities. While they can be found in small numbers on other mammals, the poor grooming practices of moose mean that moose are the primary host responsible for fluctuations in tick numbers. In other words, high numbers of moose are required to support large numbers of ticks. Most of Vermont outside of the Northeast Kingdom has never had enough moose to have enough winter ticks to cause population-level impacts.

Do winter ticks affect other animals?

Winter ticks are commonly found on deer, bears, coyotes, and many other mammals. However, because of these animals’ grooming practices, the number of ticks on any individual is usually limited to a few dozen or perhaps a few hundred at most. Winter ticks are also frequently found on livestock.

Why is the abundance of winter ticks related to the abundance of moose?

While winter ticks can be found on other mammals, those animals are better groomers and relatively few ticks will make it through their entire lifecycle without being dislodged from the host and dying. Moose are notoriously poor groomers, presumably because they did not evolve with external parasites like ticks. As a result, moose can carry far more winter ticks than other potential hosts and, therefore, the density of moose on the landscape is the primary factor affecting winter tick numbers.

Winter tick larvae cannot move more than a few feet, and if they fail to find a host before winter they die. As a result, larval ticks are dependent on a moose (or another host) walking past them. With fewer moose on the landscape, it is less likely that a moose will walk by a waiting cluster of winter tick larvae in the fall. Additionally, since a smaller number of moose will collectively pick up fewer ticks, fewer adult winter ticks will drop off in the spring to lay eggs, and there will be fewer tick larvae seeking a host the following fall.

Do winter ticks pose a risk to humans?

No. Winter ticks do not transmit any diseases that affect humans. Since they are a single-host tick, the adults are only found on the host animal – they are not on vegetation where a human might come in contact with them. A person could pick up larvae in the fall, but they are easily washed off in the shower or will drop off on their own.

Can’t moose or their habitat be treated to kill winter ticks?

This is a logical question that usually stems from us treating our pets for ticks. Moose are not pets or livestock, they are wild animals.

Reducing winter tick numbers directly, either by treating moose or the landscape with some form of acaricide (a pesticide specifically for ticks) or fungal pathogen (there are some naturally occurring fungi that can kill ticks), is not currently a viable option. Research in this area is ongoing, but the realities of treating an entire landscape or a sufficient portion of the moose population make it unlikely that this will be a practical option in the near future.

Further, treating ticks does not kill all of them and provides them an opportunity to adapt to the treatment and develop resistance. As long as there is a high density of moose on the landscape, tick numbers will simply increase again when treatments stop or when the ticks become immune to them.

Introducing animals that consume ticks (e.g., guinea fowl or opossums) is also not a viable option. Aside from the potential consequences from introducing a new animal into an area, and the fact that they could not survive the winter in that part of Vermont, they simply would not be effective at reducing winter tick numbers. The life cycle of winter ticks results in minimal opportunity for them to be predated. Adult ticks essentially only occur on the host, not on vegetation, and larval ticks are very small and either in the leaf litter or relatively high up on vegetation.

Lastly, we may dislike ticks because we find them unsightly or are concerned about diseases they may carry (remember, winter ticks do not carry those diseases), but we must remember that they are a native species just like moose. We just need to find the appropriate balance between winter ticks and moose.

Moose Population

How many moose are there in Vermont?

About 2,100.

Is the population increasing or decreasing?

Generally, the population appears to be stable. As with any species, population performance is influenced by many factors, including habitat quantity and quality, the impacts of diseases and parasites, predation, hunting, and other sources of mortality. This means, at any given time, moose in some parts of Vermont may be doing better than those in other areas.

Are Vermont moose healthy?

No. While Vermont moose are free of major diseases like Chronic Wasting Disease, they suffer from a couple significant parasites (brainworm and winter tick) and a general lack of quality habitat. Habitat quality for moose is directly related to the amount of young forest habitat, which provides the large quantities of forage moose need. Young forest habitat is increasingly rare in much of Vermont.

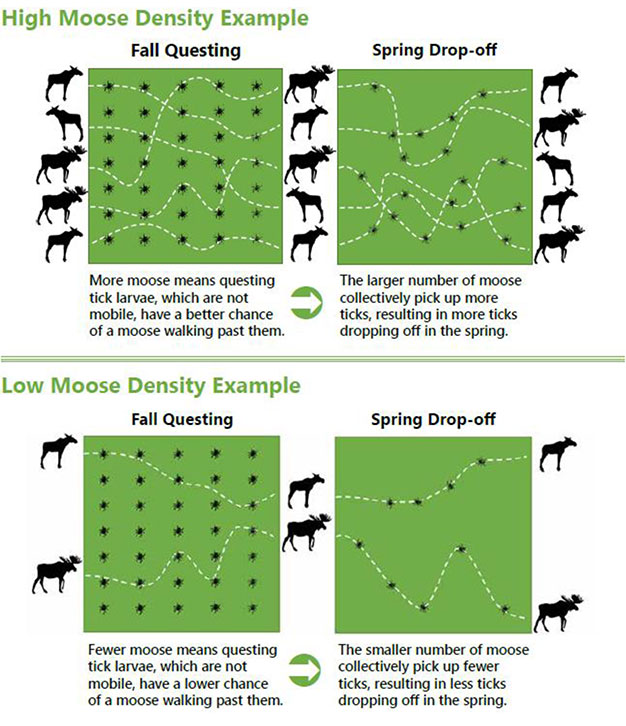

WMU E, in the northeast corner of the state, is different. This region has a colder climate than the rest of Vermont, which is more favorable to northern species like moose. It also has low deer densities which limit the prevalence of brainworm. Perhaps most importantly, it has, by far, the highest quality moose habitat in Vermont due to extensive industrial timberlands. However, moose in WMU E are in the poorest health due to impacts from winter ticks. Health measures like body weights and reproductive rates have declined substantially over the past 15 years and are currently at very low levels.

Why are there fewer moose today than 15 years ago?

First, some historical perspective. Prior to European settlement, Vermont was 95% forested and moose were common throughout much of the state. Native Americans and European colonists killed moose opportunistically throughout the year for food and fiber. As Vermont’s human population grew, the conversion of forests to agriculture and the unregulated hunting of moose in the 18th and 19th centuries resulted in their disappearance from the state.

Moose began to reappear in Vermont during the 20th century as hill farms went out of business and forests gradually returned. By 1980, 80% of Vermont was again forested, and moose were regularly seen in Essex County. The absence of predation by mountain lions, wolves, or humans allowed rapid population growth. By 1993, moose were abundant enough to support a limited, regulated hunt which eventually expanded to 78% of the state.

Boosted by a spruce budworm outbreak in the 1980s and subsequent large-scale timber harvesting, the moose population experienced significant growth through the 1990s and early 2000s. At its peak in the early 2000s, the high moose population was causing significant damage to forest regeneration in some areas of the state, particularly the Northeast Kingdom, and the health of moose was declining as a result.

Several factors are responsible for the decrease in the moose population over the past 15 years.

First, the department issued large numbers of moose hunting permits for several years to deliberately reduce the moose population in the Northeast Kingdom so it was more in balance with the available habitat. Permit numbers were greatly reduced in the early 2010s to stabilize moose numbers, but numbers continued to decline for several reasons.

In WMU E (essentially Essex County), which has always had much higher moose densities than the rest of Vermont, the primary factor limiting the moose population since 2010 has been the winter tick. Due in part to their limited grooming, an individual moose can be infested with tens of thousands of ticks. Such heavy tick loads can kill more than 50% of moose calves in the late winter and early spring. Although they don’t usually kill adult moose, the stress from heavy tick loads causes them to be in poor condition and produce fewer calves. Importantly, winter ticks can only reach problematic levels in areas with high moose densities.

Throughout the rest of Vermont, the reasons for moose population declines are less clear and likely more complex. Brainworm is more common in these areas and may be increasing. Brainworm commonly infects white-tailed deer, which evolved with the parasite and suffer no ill effects. As a result, areas with higher deer densities tend to have a greater prevalence of brainworm. When brainworms infect moose, the result is usually fatal for the moose. Moose population declines associated with brainworm have been documented in areas where deer densities exceed 10 deer per square mile. Deer densities in most of Vermont exceed 10 per square mile, except for WMU E and some remote, higher-elevation areas.

Another important factor is the lack of young forest habitat. Moose require large quantities of woody browse and do best in areas with large amounts of young forest habitat that provide abundant browse. Young forest habitat is increasingly rare in much of Vermont.

Lastly, the loss of a thriving source population in WMU E and possibly New Hampshire has likely had an effect. Fifteen years ago, those areas were producing large numbers of moose every year, many of which dispersed out to other areas. This likely provided an important source of moose – and boosted moose numbers – across much of the rest of Vermont.

Have moose populations declined in other states?

Yes. Moose populations have recently declined across the southern portion of their range due to various effects of climate change. In the northeast, populations in New Hampshire and much of Maine have experienced similar declines as Vermont, for the same reasons.

Why is WMU E so different from the rest of Vermont?

WMU E is part of a larger region of prime moose range in New England that extends through northern New Hampshire and much of Maine. This area has a colder climate with longer winters, low deer densities, large blocks of forest, and an abundance of young forest from commercial timber management which allows it to sustain higher densities of moose.

- Based on current (2022) population estimates, a little more than half of all moose in Vermont live in WMU E. Worded differently—there are more moose in WMU E than there are in the rest of Vermont combined.

- The density (2021–2023 rolling average) estimates in WMU E1 and E2 is 1.29 and 1.56 moose per square mile, respectively. No WMU outside of the Northeast Kingdom ever reached a density of 1 moose per square mile.

Moose Hunting

Why is the department proposing to hunt moose?

The department wants to reduce the moose population in WMU E to reduce the abundance of winter ticks. This will reduce the impact of winter ticks on the health of moose and result in a healthier moose population. Research indicates that winter ticks rarely impact moose populations at densities less than 1 moose per square mile and have no impact at densities less than 0.75 moose per square mile. The 2023 (2021–2023 rolling average) density estimates for WMU E1 and E2 was 1.29 and 1.56 moose per square mile, respectively.

The department is not proposing to hunt moose in other parts of Vermont. Moose numbers in those areas are below established population objectives and are not impacted by winter ticks.

Why doesn’t the department want the population to grow?

The department wants the moose population to grow in most of Vermont, just not in WMU E. That’s why the department is not proposing any hunting of moose in those areas. Allowing the population in WMU E to grow, or even remain at the current level, will perpetuate the negative impacts of winter ticks and result in unhealthy moose for decades. This would be inconsistent with the department’s established objective of managing for a healthy moose population.

What would happen if a moose hunt didn’t occur?

In the absence of hunting, moose numbers would remain stable or possibly increase in WMU E. Importantly, for moose in WMU E, this means winter ticks would continue to impact moose health for decades. The resulting chronic stress, low birth rates, and high calf mortality may prevent the population from growing, but moose will be less resilient to diseases, parasites, and environmental variation, which could cause the population to destabilize. Maintaining a healthy, stable, and sustainable moose population requires action to improve moose health. Conducting a moose hunt allows for responsible utilization of the moose population, a relatively quick death for those animals that are killed by hunters, and a preferable end result—healthy moose!

Why so many permits?

The harvest of adult females has the greatest impact on future population size. The department is attempting to harvest roughly 4% of the adult female population in WMU E, which would slowly reduce the population to the target density over a period of several years. The department considers past success rates and harvest sex ratios for different types of permits when determining the number and type of permits needed to achieve the desired harvest. The 180 permits (80 either sex and 100 antlerless-only) recommended for 2024 are expected to result in the harvest of 94 moose (range: 73–117), including 37–56 adult females.

This permit recommendation is necessary to effectively manage the moose population in WMU E. The results of the moose study clearly demonstrate that moose in WMU E are in poor health due to heavy winter tick loads, and it now appears that moose numbers in WMU E may be increasing. Reducing the number of moose is necessary to reduce the impacts of winter ticks and improve the health of moose in that region.

Why not fewer permits? Or more permits?

The recommended permit allocation and resulting cow moose harvest will take several years to reduce the moose population in WMU E to the target density. This assumes tick impacts continue at their average level over the past 4 to 5 years and there is no improvement in moose survival or reproductive rates. Issuing fewer permits and harvesting fewer cow moose would not ensure that the population would be reduced.

Ideally, moose health should be improved as quickly as possible, and increasing the harvest of cow moose might help achieve that goal. However, there are many uncertainties when managing wild, free-ranging populations of moose. Low survival and birth rates observed from Vermont moose, and broader, regional population declines in moose justify a cautious approach at this time. The recommended harvest reduces the population slowly enough to allow for future adjustments to the harvest, if necessary, even if the actual current density of moose is lower than current estimates. Management of moose in WMU E and throughout Vermont must continue to be adaptive and respond to new information as it becomes available. If continued monitoring indicates that health, survival, and birth rates remain poor, and the moose population in WMU E remains above the objective, a more aggressive approach may be necessary to improve the health of the region’s moose in the future.

Will moose numbers in WMU E increase after tick impacts are reduced?

WMU E has, by far, the best moose habitat in Vermont. If tick impacts are reduced and moose health and survival improve, the population would be capable of increasing.